Baited stretches: should I use a lick or a carrot?

How does stretching work?

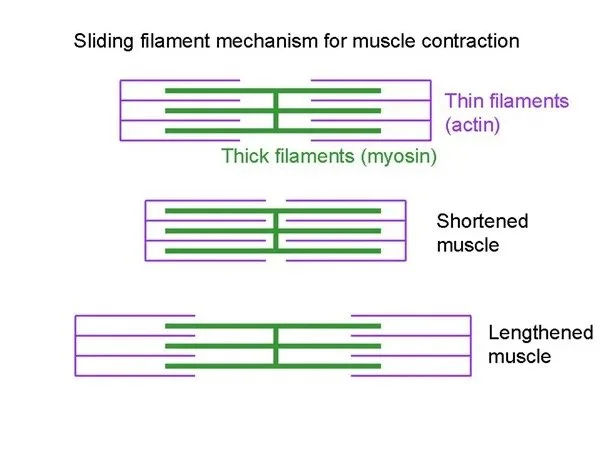

Stretching is defined as elongating something (in this case muscles and tendons) beyond its natural state at rest. It is a common misconception that the individual muscle fibres themselves stretch like an elastic band, however this is not true. What actually happens is that there are two types of filaments, known as actin and myosin, which at rest overlap slightly. When a stretch is applied, the overlap between these fibres reduces, allowing the muscle to increase in length. This process is not instantaneous, because an injury-defence mechanism, known as golgi tendon organs, sat in the junction between muscles and tendons need about seven seconds before allowing the muscle to relax and lengthen.

Why is stretching important?

There are many reasons to stretch, including improving flexibility and preventing contracture, which will help to increase performance. There will also be additional benefits depending on whether the stretching is performed before or after exercise.

Before exercise stretching will:

Start sending impulses through the nervous system to help ‘wake it up’

Reduce adhesions that may be causing tightness and discomfort, allowing the horse to move more freely when ridden

Briefly compress blood vessels, then allowing fresh blood to rush in which contains higher volumes of oxygen needed for exercise

It is important to note that stretching should not be done ‘cold’, so if stretching before exercise then the muscles need to be warmed up first through gentle massage or with heat packs

After exercise stretching will:

Remove waste products, such as lactic acid, at a faster rate by bringing fresh blood in the same way as above, which will reduce delayed onset muscle soreness (DOMS)

Aid realignment of muscle fibres

Reduce tension that may have crept in from incorrect use or overuse of muscles

Does it really make a difference if I use a lick or a carrot?

Surprisingly, yes it does! This is because (with most horses!) they are so food orientated that they will be snatching at the carrot to try and get a bite, and then return their head to neutral when chewing before turning to snatch at the carrot again. Whereas if you use a lick the head and neck position remains a lot more consistent during the stretch, allowing the stretch to be held for longer (remember it needs about seven seconds for the stretch reflex to even kick in!). The snatching action seen when reaching for the carrot is known as ballistic stretching, which can actually cause injury as the muscle is being forced to constantly lengthen and shorten before it is ready to, causing tightness to creep in. Whereas the consistent stretch seen with a lick is known as dynamic stretching, and is much more controlled. It also allows you to easily intensify the stretch gradually by bringing the lick further towards the horses hindquarters, or to lessen the stretch if your horse is struggling.

References

ACROPT (2017) The (basic) physiology of static stretching, ACRO: Physical Therapy, Massage Therapy & Aerial Fitness. Available at: https://www.acropt.com/blog/2017/8/10/the-physiology-of-stretching (Accessed: 28 August 2025).

Farinelli, F., de Rezende, A.S.C., Fonseca, M.G., Lana, Â.M.Q., Leme, F. de O.P., Klein, B. de O.N., Silva, R.H.P., de Abreu, A.P., Damazio, M. de J. and Melo, M.M. (2021) ‘Influence of Stretching Exercises, Warm-Up, or Cool-Down on the Physical Performance of Mangalarga Marchador Horses’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 106, p. 103714. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2021.103714.

Frick, A. (2010) ‘Stretching Exercises for Horses: Are They Effective?’, Journal of Equine Veterinary Science, 30(1), pp. 50–59. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jevs.2009.12.001.

Herbert, R.D. and Gabriel, M. (2002) ‘Effects of stretching before and after exercising on muscle soreness and risk of injury: systematic review’, BMJ, 325(7362), p. 468. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.325.7362.468.

Knudson, D. (2020) ‘The biomechanics of stretching’, Journal of Exercise Science and Physiotherapy, 2, pp. 3–12. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.865585862968627.

Large Animal Clinical Sciences (2021) Equine Carrot Stretches, Veterinary Medical Centre. Available at: https://vetmed.tennessee.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/UTCVM_EquineCarrotStretches.pdf.

LaRoche, D.P. and Connolly, D.A.J. (2006) ‘Effects of Stretching on Passive Muscle Tension and Response to Eccentric Exercise’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 34(6), pp. 1000–1007. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546505284238.

Taylor, D.C., Dalton, J.D., Seaber, A.V. and Garrett, W.E. (1990) ‘Viscoelastic properties of muscle-tendon units: The biomechanical effects of stretching’, The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 18(3), pp. 300–309. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/036354659001800314.