Making sense of pain

What is pain?

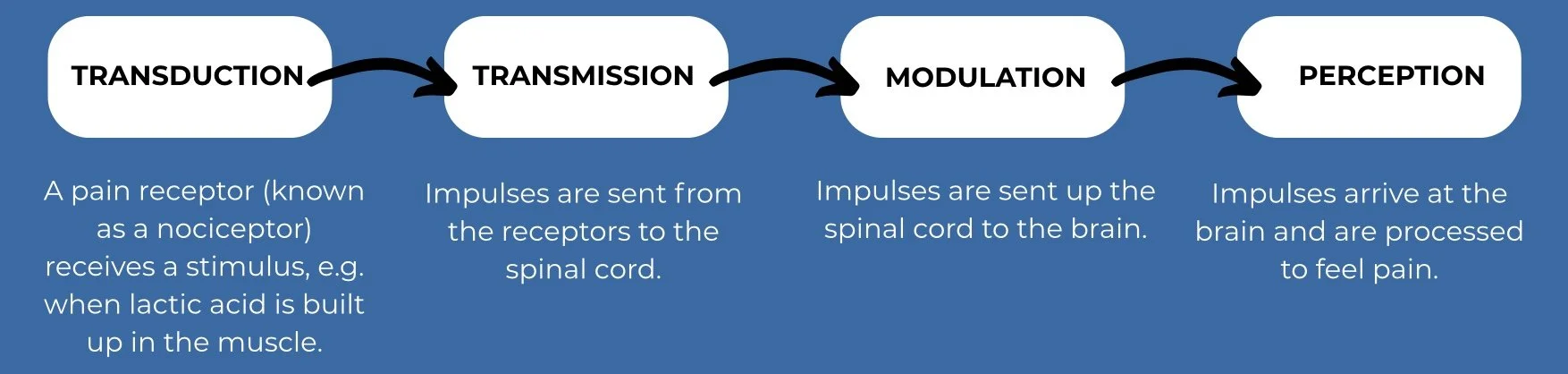

Pain is something we and our animals will all unfortunately encounter in our lifetimes, so it is important to understand how it works. There are 4 key stages that occur within the nervous system in order for an animal to process the feelings of pain. These are outlined in the flowchart below.

How can I tell that my animal is in pain?

This is a question we all wish was more easily answered, because sometimes our animals will only show the subtlest of signs. It’s a bit of an art to decipher all of the minuscule signals that animals show, but to make things easier pain ethograms have been developed. These are essentially a long checklist of behaviours that animals (species specific) may show when in pain. Typically, eight of these behaviours should be met in order to class an animal as ‘being in pain’. An example of an equine ethogram to classify pain whilst ridden is seen on the right. Seeing our pets day in and day out means that we can sometimes miss things or not be able to see the progression of issues. Therefore, it’s highly recommended to take frequent comparison videos or to have an outside pair of eyes cast a look at them to identify behaviours that might otherwise go amiss.

Most importantly, how to help?

The treatment of pain will be dependent on the reason for it, hence why consulting a vet is paramount. Once a reason has been determined, a suitable plan of action can be discussed, which may include thermotherapy (the introduction of hot or cold temperatures), electrotherapy (such as laser) and massage.

Thermotherapy reduces pain because adding heat reduces the muscle spindle sensitivity, reducing muscle spasms and therefore alleviating resulting blood vessel compression.

Electrotherapy promotes the release of anti-inflammatory compounds, reducing nociceptor compression and therefore creating more infrequent stimulations.

Massage stimulates specific touch-sensitive nerve fibres, known as alpha-beta fibres. These fibres transmit signals to the brain at a faster rate than C fibres (which are the fibres responsible for pain transmission). This means that pain signals are overridden.

References

Dyson, S. and Pollard, D. (2020) ‘Application of a Ridden Horse Pain Ethogram and Its Relationship with Gait in a Convenience Sample of 60 Riding Horses’, Animals, 10(6), p. 1044. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10061044.

Haussler, K.K. (2010) ‘The Role of Manual Therapies in Equine Pain Management’, Veterinary Clinics: Equine Practice, 26(3), pp. 579–601. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cveq.2010.07.006.

Hyytiäinen, H.K., Boström, A., Asplund, K. and Bergh, A. (2023) ‘A Systematic Review of Complementary and Alternative Veterinary Medicine in Sport and Companion Animals: Electrotherapy’, Animals, 13(1), p. 64. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3390/ani13010064.

Muir, W.W. (2010) ‘Pain: Mechanisms and Management in Horses’, Veterinary Clinics: Equine Practice, 26(3), pp. 467–480. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cveq.2010.07.008.

Reed, R.A. (2022) ‘Pathophysiology of Pain’, in Manual of Equine Anesthesia and Analgesia. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 425–430. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119631316.ch28.

Tomlinson, J.E. and Cappucci, D. (2024) ‘Modalities Part 1: Thermotherapy’, in Physical Rehabilitation for Veterinary Technicians and Nurses. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, pp. 273–286. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119892441.ch15.